The UK’s prison system acts on our behalf; are we happy with how it’s doing?

Written by Lucy Hart, Dee Norval and Guilherme Pretti.

What is prison ‘for’? And who does it serve? Though it can be uncomfortable to sit with, the criminal justice system acts on behalf of the nation’s citizens: us. The decisions being made in courts across the land are handed down in order to satisfy our needs, as victims, as potential victims and – depending on your view – as potential offenders.

So it matters that we know if it is working in its role as a public service, and for that, getting some kind of answer on what the system aims to achieve is necessary.

What is the prison system there to do?

Putting our moral positions aside for a moment, let’s look at the goals laid out by the Ministry of Justice for the prison system. Prisons exist to: “protect the public; maintain safety and order; reform offenders to prevent more crimes from being committed; and prepare prisoners for life outside the prison”.

Just like with other public services in health, employment, care and elsewhere, the prison system is assessed against its objectives, both internally and by external bodies. In the UK, much of the criminal justice system is devolved. We’ll talk about England and Wales here; the picture in Scotland (prison population ~7500) and in Northern Ireland (~1500) is fairly different.

How’s it performing?

Looking at the government’s own data, we see a mixed picture on performance – but overall, it’s not a pretty one. 2021-22 reports show that for the first pillar – essentially keeping prisoners in prison – the UK is doing just about OK. 85% of prisons achieve a positive rating on security; escapes are rare and effective security procedures are adhered to.

Safety and order within prisons is more variable. About half manage a positive rating on risk management, but levels of self-harm and suicide are substantially higher than the European median. Assault levels between prisoners and against staff fell substantially during the pandemic, where most prisoners were kept isolated for many months, but have been increasing since.

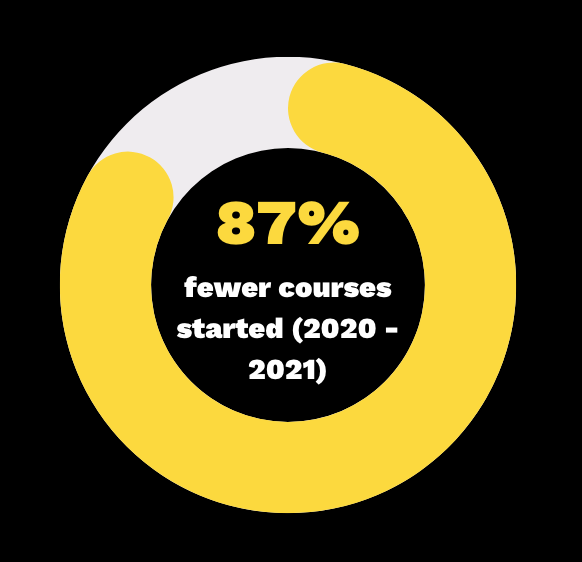

When it comes to rehabilitation for a life beyond prison the results are, however, pretty universally abysmal. “Purposeful activity”, i.e. work and education, is a key component. Less than half of prisons scored satisfactorily in prisoners being able, and expected, to engage in it. It’s a story we see repeated in the Institute for Government’s performance tracker, which shows that 87% fewer courses were started between 2020 and 2021; activity has been growing since but has not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels.

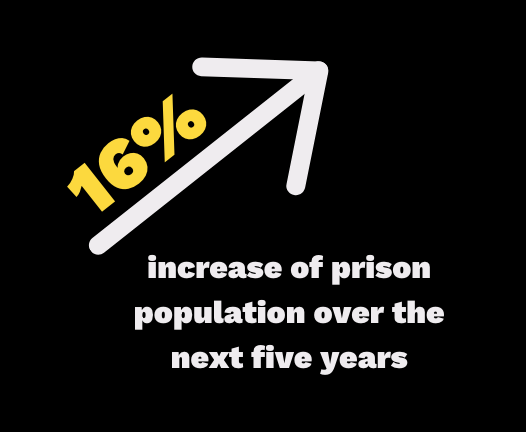

Perhaps unsurprisingly, we see the effects in life after prison; just 4% of prisons are achieving the target for employment at six weeks following release, and only a fifth of offenders are employed 6 months later. Over 80% received unsatisfactory scores for rehabilitation and release planning. With the prison population set to increase by 16% over the next five years, we can expect more offenders being released with little success in rehabilitation.

Why is nothing changing?

This isn’t new news, and the government has many plans for further reform. But if we approach this from a wider angle, we see that when other government services are poorly delivered and ineffectual, there is public protest over inefficient use of taxpayers’ money. There are well reported enquiries. There are large scale campaigns. So why isn’t that happening here?

Public service users are often the first to spot and escalate issues, but in prisons, offenders are incredibly limited in the impact they can have. They have no access to the internet, and a lot of red tape can stand in the way of the paper-based complaints system. Civilian campaigns in the prison space are often driven by family members of a prisoner, and often in the case that that prisoner has died, such as the family of Zahid Mubarek; that’s a huge ask for a grieving, often under-resourced family.

Journalists’ access to prisons can limit investigations that might take place in other public sectors. And perhaps the public are simply less exposed to the prison system – while there are more than 80,000 people in prison at any one time, offending and reoffending tends to stay within the same small circle. There are social factors, too – most prisoners are from working class backgrounds; many MPs and those who have their ear are not.

What’s blocking change in society?

For us, the biggest barrier to change outside prison walls is public perceptions. Those views – often shaped by misleading narratives – impact how people vote but also how likely they might be to protest the failures of the system.

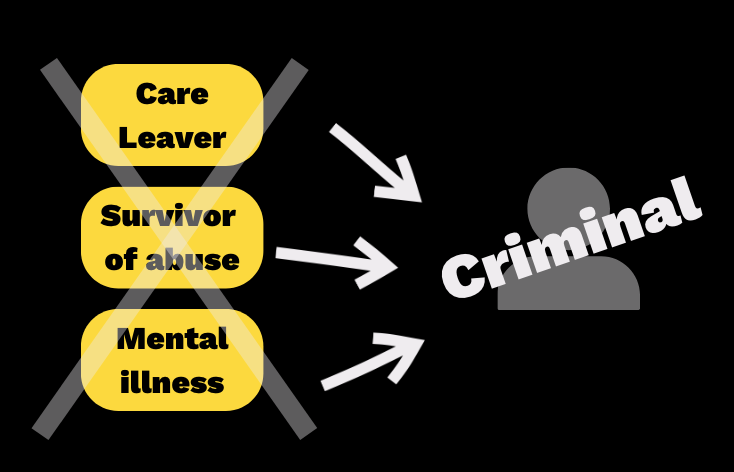

Many people’s view of prisoners takes quite a children’s book position on morality – the bad robber – and there are few opportunities to influence that stance. The term ‘prisoner’ or ‘criminal’ puts an opaque sheet in front of the disadvantages that individual may have faced; where before their incarceration we may have seen them as a care leaver, someone with mental illness or a survivor of abuse, and offered the compassion that comes with those labels, we now tippex them out.

In media portrayals, we hear shock stories of particular crimes and take those individuals as representative of the general prison populace, despite this being far from the typical experience. Prisoners are for the most part physically out of sight, and even when released and in employment, they may not choose to openly share their story. So people are unlikely to know that employers who have hired ex-prisoners believe them to be ‘motivated, reliable, good at their job and trustworthy’.

And more than in other public services, the Ministry frequently involves itself in prison service delivery, due to “the extent of perceived political risk associated with prisons”. The changes we see pushed through in prison reform are frequently the result of specific stories with high press coverage – such as the parole board changes in 2022 after public outcry surrounding the release of Colin Pitchfork and John Worboys – than statistical reality.

What’s blocking change inside prisons?

So let’s look within the prisons – what are the blockers there for rehabilitation being carried out? While staffing levels are obviously challenging, our founder Dee believes that the primary obstacle is one of culture, or mindset: “Security is paramount and is held above other goals, including rehabilitation. Rehabilitation requires people to be let out of their cells to take part in activities, but you have a situation now where the security-first mindset would say no to that, to avoid violence.

Those aims shouldn’t be mutually exclusive; it’s important that guys in prison feel secure, so they can apply themselves in a way they can’t if they’re scared. But what I’m talking about is a mindset which starts from ‘it can’t be done’ rather than ‘how can we make this work?’”

The staffing challenge (employees leave at roughly the same rate as they’re recruited) is in large part driven by this but also drives it; great people come to work in the system with ambitions to improve the lives and prospects of offenders, but find themselves continually blocked and worn down – and less well paid than, for example, in the police. Understaffing and a high proportion of new staff (over 20% of prison officers have been in the job for under two years) have contributed to the continuation of restrictions, where many prisoners are being kept in cells for ~22 hours each day.

In many ways, the ‘security first’ mindset makes sense. As Dee puts it, “Prisons are assessed for the worst thing that has happened; they’re remembered for security breaches, not success rates.” Yet in turning all their attention to preventing that, prisons don’t pay enough to the tens of thousands of people being released each year, half of whom are likely to reoffend.

Where safety concerns are handled sufficiently to enable the provision of employment and education, we stumble across another mindset barrier in the delivery of those services. Education provision was restructured in 2018 after poor results, with a new framework to “meet the needs of prisoners, making it more likely to lead them to a positive employment outcome on release.” Yet all contracts were awarded to just four providers, all of whom were incumbents, and few improvements have been seen.

Governors are now able to contract bespoke training with organisations directly, including voluntary ones. But as we’ve experienced, the start-up costs for delivering services for prisons can be prohibitively high; you need sufficient staff time to work out workarounds for the lack of WiFi, the limits on paper handouts, the fairly constant lockdown. Where contracts are fairly short, it is often not worth an SME’s investment in the bidding process.

The assessment of providers is patchy, at best. Most are judged by attendance, and sometimes qualifications achieved, but are rarely asked for feedback on the course, or even results in terms of employment. The 2022 Prison Education report iterates the many shortcomings of current education provision, from not adapting to the needs of prisoners with previous negative experiences of education, to the absence of digital skills training, to the lack of data about its impact beyond release.

This means we could well be – and likely are – spending money on courses that objectively aren’t working, or even making things worse. As Matthew Coffey, COO at Ofsted, puts it, “There are no consequences for failure in this respect at all … In every other walk of Ofsted’s life there are consequences… I have been at Ofsted since 2007 and have never seen a prison held to account for poor provision.”

What might help?

We’ve seen some signs of change that we think might start pushing these barriers aside, in and out of prison. Unlocked Grads – like Teach First for prison officers – is bringing innovative, enthusiastic staff into prisons. Small enterprises like ours are looking to establish best practices for how an organisation can operate in the prison space, and doing what we can to reduce the impact of red tape for those coming after us. And the increased powers of governors allows some prisons to tread new ground in innovative approaches to training and education.

What’s the verdict?

If we think of ourselves as stakeholders of the prison system – due benefits thanks to the money we’ve put in as taxpayers – surely there can be no other judgement than that its performance is deeply unsatisfactory. It is far from meeting the standards that it has set for itself in terms of protecting the public through reform. And, perhaps even worse, there seems to be little redress.

As the late ex-offender and prisons correspondent Eric Allison put it, “What about the boys, and the men and the women who come out [of prison] boiling with rage? Where’s that rage going to go? I’ll tell you where it’s going to go; it’s going to go on society. So that’s why it doesn’t work.” How we treat people in prison directly affects how they behave – and the impact on us – when they get out. We must demand of our prison system to do better. If not for them, then for ourselves.